In her own words, Harriet gives us a glimpse into the past as she shares her life with the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union and the landmark decisions that changed history.

I came to Hawai'i in 1939 -- with a dream of Paradise -- with my licenses to practice law in both Indiana and Massachusetts. I discovered that Hawai'i was a feudal society with no Unions and with indentured labor forming a multi-ethnic culture. Five large corporations owned the sugar and pineapple plantations on all of the Hawaiian Islands, and they brought in workers from many countries, paying them the lowest of wages of $15 a month for 10-hour days or 2 cents an hour in 1891, keeping each ethnic group apart at work and at home, in order to control their lives.

I came to Hawai'i in 1939 -- with a dream of Paradise -- with my licenses to practice law in both Indiana and Massachusetts. I discovered that Hawai'i was a feudal society with no Unions and with indentured labor forming a multi-ethnic culture. Five large corporations owned the sugar and pineapple plantations on all of the Hawaiian Islands, and they brought in workers from many countries, paying them the lowest of wages of $15 a month for 10-hour days or 2 cents an hour in 1891, keeping each ethnic group apart at work and at home, in order to control their lives.

In order to practice law in the Territory, I had to wait one year as a residency requirement before I could take the bar exam. The wages were so low that my then- husband, a University of Hawai'i English teacher, could n

ot support me. By necessity, I obtained a teaching position at Honolulu Business College teaching English and Mathematics to local students who were wonderful, but their pidgin English was difficult to understand. After six months I got a job as a secretary with the Big Five law firm Stanley, Vitousek, Pratt, and Winn. I was honest about my intentions to work for them while using their library and law books to study for the bar so I could open my own practice and "help the people of Hawai'i."

On December 23, 1941, I received my Territory of Hawai'i license to practice law; Pearl Harbor had been attacked by the Japanese 16 days earlier. I was granted my Federal license on May 14, 1942 and Attorney Vitousek and his associates changed my status to that of attorney and put my name on their stationery. However, there was no legal work in the courts which were closed because of Martial Law in Hawai'i.

In an attempt to eliminate Martial Law in Hawai'i, I went to Washington, D.C. to find legal work. A friend, Clifford O'Brien, a labor attorney who the ILWU Local 142 had sent to Kauai, gave me a letter of introduction to Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon who was head of the National War Labor Board. I was the first attorney to work for the War Labor Board in the Fall of 1942. The War Labor Board's role was to enforce the employers' payment of 40 cents per hour, the minimum. wage set by then President Roosevelt's law.

In the Spring of 1944, I had an opportunity to work for several different Union leaders whom I had become acquainted with while working at the War Labor Board, and Harry Bridges of the ILWU Local 142 was the one I was most interested in because I always wanted to come back to Hawai'i. The ILWU Local 142 Representative, Bjorne Halling, recommended me to Bridges as his replacement and as the Union lobbyist for the ILWU Local 142 and the Committee for Maritime Unity which consisted of several unions. I met Bridges when he came to Washington, D.C. to interview me for the job.

Bridges took me to all the committee hearings where he spoke about higher wages and better job conditions. I made all his appointments with committee senators and chairmen and accompanied him everywhere, even to the meeting where the CIO kicked out the ILWU Local 142. Harry Bridges was my mentor. Bridges always kept me abreast about what was happening in Hawai'i, much of which I already knew from having worked at a Big Five firm, specifically with Winn who represented the employers. While at Stanley, Vitousek, Pratt, and Winn, I often read the Voice of Labor written by Jack Hall in Kauai.

In Hawai'i, after Martial Law was lifted, the ILWU Local 142 began to organize sugar and pineapple. Harry Bridges asked me who the Regional Director of the ILWU Local 142 should be. With no doubt in my mind, I recommended Jack Hall. I had met him briefly while working at the Big Five firm and I had read his excellent writings, and I recognized early on that Hall was a natural labor leader.

In Hawai'i, after Martial Law was lifted, the ILWU Local 142 began to organize sugar and pineapple. Harry Bridges asked me who the Regional Director of the ILWU Local 142 should be. With no doubt in my mind, I recommended Jack Hall. I had met him briefly while working at the Big Five firm and I had read his excellent writings, and I recognized early on that Hall was a natural labor leader.

In October 1946, I received an urgent SOS from Harry Bridges and Jack Hall to return to the Islands to defend 150 Union sugar strikers charged with criminal offenses as a result of Hawai'i's first peaceful plantation strike -- the only successful plantation strike in the history of the Islands.

This is the situation that confronted me when I arrived in the Territory:

- On Kauai, 12 Union members were indicted for 2 year prison terms for criminal contempt of a restraining order against picketing issued by Judge Rice.

- On Maui, 79 Union members employed by Maui Agricultural Company were indicted for unlawful assembly, a felony in the Territory punishable by 20 years imprisonment or a $1,000 fine.

- On Maui, 23 Union members employed by Pioneer Mill were Charged with riot, unlawful assembly, conspiracy, and assault and battery.

- Twelve Union members were charged with contempt of a restraining order against picketing issued by Judge Wirtz.

- Nine of the Union members from Maui were charged with misdemeanor and assault and battery, malicious injury and threatening to disturb the peace.

I disposed of 32 cases against Union members from Maui with fines or suspended sentences. In the case of the 79 Maui members charged with unlawful assembly, I urged the court to declare the statute unconstitutional because it violated the constitutional rights of free speech and assembly guaranteed to all citizens of the United States. Judge Writz of Maui, in a lengthy opinion, refused to declare the statute void, and I appealed to the Territorial Supreme Court.

In my brief, I pointed out that the Supreme Court of the United States said that the right of workers to picket was part of the rights of free speech and assembly guaranteed by the Constitution.

"If this unlawful assembly and riot statute, which collected dust for almost 100 years without being used, is turned against workers in the Territory, the right to picket would be destroyed because the penalties provided in the statute were so severe that fear would restrain the exercise of the right to picket."

Old-time Hawaiians claimed that the unlawful assembly statute was first passed in 1869 to keep Hawaiians from getting together and complaining about being robbed of their lands. I pointed out to the Supreme Court that the Norris-LaGuardia Act guaranteed to the workers in the Territory the right to engage in mass picketing and that the so-called unlawful assembly was in reality a mass picket line which took place at Paia, Maui, on October 15, 1946.

Old-time Hawaiians claimed that the unlawful assembly statute was first passed in 1869 to keep Hawaiians from getting together and complaining about being robbed of their lands. I pointed out to the Supreme Court that the Norris-LaGuardia Act guaranteed to the workers in the Territory the right to engage in mass picketing and that the so-called unlawful assembly was in reality a mass picket line which took place at Paia, Maui, on October 15, 1946.

I also pointed out to the court that in most states, the maximum penalty for unlawful assembly was from 3 to 6 months, and that the unlawful assembly statute of the Territory was never intended to apply to Union picketers. In the case of the 12 Kauai strikers charged with contempt of an ex parte restraining order against picketing issued by Judge Rice, I got a preliminary injunction against Attorney General Tavares restraining him from prosecuting these cases until the Federal Court could determine whether the strikers were being deprived of their rights guaranteed them by the Constitution and Laws of the United States.

The Attorney General, Mr. Nil Tavares, who had just resigned to join the employer law firm of Vitousek, Pratt, and Winn, took this case out of the hands of the local police and the elected County Attorney of Kauai, and sent two of his deputy attorney generals to make the investigation of the mass picket line which resulted in the indictment. Tavares argued before Judge McLaughlin that mass picketing was illegal in the Territory and that Judge Rice had power to issue an ex parte restraining order against picketing. I claimed that because of the Norris-LaGuardia Act and rights guaranteed by the Constitution, the Union members had a right to picket and that Judge Rice's order was void. Union members were being deprived of rights guaranteed them by the Laws and by the Constitution of the United States in being forced to defend themselves against charges of criminal contempt for exercising their right to picket.

The case of the 12 Union strikers from Maui charged with contempt of court was, I believe, a void restraining order against picketing, and I appealed the adverse decision of the Supreme Court to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco. After Judge Wirtz of Maui, and the Supreme Court of the Territory refused to hold the unlawful assembly law unconstitutional, and after Judge Cristy overruled the challenge of the 1947 Maui County Grand Jury, I sued the Attorney General and the law enforcement officers of Maui County in the Federal Court. I asked the Federal Court to stop these prosecutions and to declare those old laws unconstitutional and the method of selecting juries illegal.

In 1947 there occurred an industry-wide strike in the pineapple industry. Widespread actions by the employers to restrain picketing were countered by efforts to enjoin the activities of the employers in the Federal courts under the civil rights statute. I represented the defendants

In 1947 there occurred an industry-wide strike in the pineapple industry. Widespread actions by the employers to restrain picketing were countered by efforts to enjoin the activities of the employers in the Federal courts under the civil rights statute. I represented the defendants

[ILWU Local 142] in the actions brought by employers and the plaintiffs in the actions brought under the civil rights statutes. The ILWU Local 142 members returned to work.Three Federal judges heard the cases-Judge Metzger of the Federal District Court for Hawai'i, Judge Biggs of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals in Philadelphia, and Judge Harris of the Federal District Court in San Francisco. The court ruled in my favor and against the Attorney General.

The decision held the following:

- That the unlawful assembly act is unconstitutional because it lays too great emphasis on peace as distinguished from freedom.

- That the conspiracy statute was unconstitutional because it was too vague and uncertain.

- That those statutes had in effect been used as a weapon in the employers' struggle to get labor as cheaply as possible. Strikes, peaceful picketing and freedom of speech are lawful weapons of labor, the court said. So long as those two laws hung over labor's head, good relations between labor and management were impossible. To show the serious threat to the Union, the court pointed out how the laws had been used in the past and said that if the full 20 years prison term provided by the law were imposed on any substantial number of Union men "labor on the Islands of Hawai'i may, with a measure of justification conclude that the processes of the law have been employed to reduce its members to virtual peonage."

- That the criminal prosecutions were not brought in good faith. The court reached this conclusion because of the mass arrests during the sugar and pineapple disputes, the excessive bails required in labor cases, because the statutes had been used only against labor and for trivial offenses. The court found "that the criminal proceedings complained of are being carried on for the purpose of attack upon the labor movement rather than for the ends of justice … The record seems to indicate that the unlawful assembly and riot act has been employed as a club to beat labor and that the conspiracy statute is an apt instrument to the same end."

- That criminal prosecution should be handled by regular law enforcement officers. The court strongly condemned the practice of permitting the employment of special prosecutors, citing the fact that the HSPA paid special prosecutors during the 1924 Filipino strike. The court said, "It is an undesirable custom of long standing whereby … the administration of public justice has in effect been brought into the hands of the private property owner."

- That the 1947 Maui Grand Jury was illegal. The court held illegal the method employed by the Maui County jury commissioners in choosing juries. It found that there was a deliberate, substantial exclusion of wage earners and a deliberate substantial weighting of the jury in favor of businessmen. It found that Filipinos were deliberately excluded from jury service. It reached the conclusion that the 1947 Maui Grand Jury did not fairly represent a cross-section of Maui County, and that Judge Cristy had not given the Union members a full and fair hearing on the challenges before him.

- Since 1900, when Hawai'i became part of the United States, hundreds of working men had been sent to prison under those two laws now stricken down by my efforts. During the 1924 Filipino strike, which broke the back of labor for 13 years, 60 strikers were sentenced to prison for 4 years or more under those laws. This decision came too late to help the thousands of workers who had in the past struggled, organized and struck for decent living wages. The system of stacked justice which broke all strikes is responsible for the miserably low wages of workers in Hawai'i until after World War II and the organization of the ILWU Local 142.

This decision helped make real progress toward the democratic goal of equal justice for all people, labor and capital alike. But its value will be lost if the people do not learn about the decision and understand it. It can be lost if people elect, or tolerate the appointment of, law enforcement officers who by their conduct show bias and prejudice on the side of special interest groups.

The responsibility rests with the people to see that stacked justice never again masquerades in Hawai'i as law and order.

In 1949, there was a strike of the ILWU Local 142 Longshoremen. The Territorial Legislature passed a strike-breaking law specifically against the Union Longshoremen. I and my law partner, Myers Symonds, unsuccessfully filed a civil rights suit to declare the law unconstitutional. I got the court to grant permission for one picket. Harry Bridges came to support the Longshoremen. This one picket was all that was necessary for the Maritime Unions to refuse to cross Bridges who was the picket line. The Maritime Union members were charged by ship owners with mutiny. I defended and won the case for the Maritime Union members taking the case all the way to the Ninth

Circuit Court.

My partner and I represented, in the House Committee on Un-American Activities and at the Senate Committee, our clients who did not exercise their constitutional rights to speak. Thirty-nine witnesses were call in by the two committees, and were acquitted.

From August 31,1951 through June 20,1953, I was one of the counsels for the defendants in the only prosecution in the Territory of Hawai'i for conspiracy to violate the Smith Act, United States v. Fujimoto, et al. Jack Hall, one of the defendants, was the International Regional Director of the ILWU Local 142. All seven defendants were convicted by the jury.

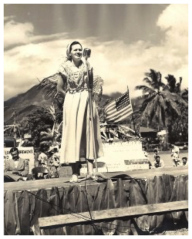

While the case was in progress, Jack Hall asked me to fly to the Island of Hawai'i with him and tell the ILWU Local 142 workers what was going on in the case. I traveled 180 miles from the Federal court and made a speech to the ILWU Local 142 plantation workers at their county meeting. I told the workers what the witnesses for prosecution testified about things happening all over the world and in Hawai'i when Hall was 5 years old and other similar information. A reporter made notes of my speech. Federal Judge Wigg, upon learning of the reporters notes told the Hawai'i Bar Association to investigate and charge me for contempt of court. Charges were made and a numbers of hearings were held. Attorney John McTernan of Los Angeles was hired by the ILWU Local 142 to represent me.

The Territorial Supreme Court made a new ruling against me restricting me to never interview a juror after a trial, to do so would be at my peril. That court suspended my license for one year which Would require me to take the Hawai'i bar exam again. My attorney applied for and received from the Ninth Circuit Court restoration of my license while the case was on appeal. In reality, I stopped practice for only one month.

The appeal of my case was first heard by three judges of the Ninth Circuit Court in San Francisco. The case was then referred to the full court of seven justices. The seven-judge court voted four to three against me. In re Sawyer, 260 F 2d 189, Chief Stephens dissented and joined Judge Pope and Judge Hamley in dissenting to the majority decision of. the court. Judge Pope said, "this is no ordinary case." Judge Pope found, "there is nothing in the record to support the statement" on which the Territorial Supreme Court ruled against me. Judge Pope's 32-page dissenting opinion may well have been the reason the United States Supreme Court agreed to accept the appeal.

In June 1959, "In the Matter of Disciplinary Proceedings against Harriet Bouslog Sawyer, Petitioner," 360 U.S. 622, 3 L. ed. ed1473, 79 S. Ct., the United States Supreme Court ruled in my favor five to four. This case was argued May 19 and 20, 1959 and was decided June 29,1959. The Justices in favor of me were Brennan, Chief Justice Warren, Black; Douglas and Potter Stewart. There were seven separate Opinions. The Supreme Court reversed the Ninth Circuit Court and the Territorial Supreme Court, and ordered all my costs to be paid.

One month later Hawai'i was granted Statehood by the United States.

Harry Bridges, President of the ILWU Local 142, commented publicly on Hawai'i's Statehood on July 27, 1959:

"The bringing of economic democracy to Hawai'i through the ILWU Local 142 and its contributions toward racial equality, as well as toward destroying the old feudal grip on the Islands, was without doubt, an important factor in the achievement of Statehood."

In December 1977, ILWU Local 142 honored me for my dedication to the working people of Hawai'i and conferred to me the title of Lifetime Honorary Member of the ILWU Local 142 of Hawai'i.

I am proud of my work from November 1946 to December 31, 1978 because I feel my efforts as an attorney contributed to the great achievements of the ILWU Local 142 accomplished in organizing the workers in Hawai'i on the vast sugar and pineapple plantations as well as the longshoremen. The conflict of forces led strikes to improve working and living conditions, and to put pressures on both law and custom effecting the social, civic, and political participation of the great non-white masses in the community life of the Islands.

On December 31, 1978, my associates dissolved the partnership of Bouslog and Symonds.

I am currently working on my memoirs of my lifetime dedication to making Hawai'i a better place to live.

~Harriet Bouslog

ref no:36388

Please send questions about this website to webmaster

Terms of Use / Legal Disclaimer / Privacy Statement

Site Designed and Managed by MacBusiness Consulting